I’ve an

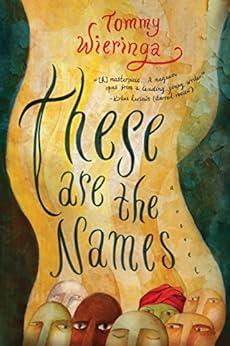

interest in Dutch culture because of my husband’s Dutch heritage so when I came

across this title by a Dutch writer in some Best Books of 2016 lists, I decided

to read it. I’m glad I did.

Alternating

chapters tell two stories which eventually merge. In a fictional Eastern European town bordering

on the Western Steppe, 53-year-old Pontus Beg, the police commissioner, searches

for meaning for his lonely life. Walking

west on the steppes is a small group of refugees fleeing poverty and

repression. Eventually, Beg meets the

migrants when they arrive in his town carrying evidence of a crime.

The novel’s

title taken from the opening lines of the Book of Exodus clearly indicates one

of its major themes: migration. The frail and starving refugees spend months

on the featureless and desolate steppes, like the Israelites who wandered for

40 years in the wilderness. They are not

identified by name; they are known as the tall man, the poacher, the young boy,

the woman, the Ethiopian, etc. Over

time, they lose their possessions and their pasts; some even lose their

lives. Even “Their footsteps were wiped

out quickly behind them.” Considering

events in Europe, this is a very relevant theme.

The human

desire to begin again, to be reborn to a new life, is emphasized. Obviously, the refugees left their homes so

they could find new lives for themselves and their families. Beg, when he sees a synagogue’s ritual bath, imagines

being immersed in it and becoming a new person:

“What a pleasant, comforting thought . . . to shed his old soul, that

tattered, worn thing, and receive a new one in its stead. Who wouldn’t want that? Who would turn down something like that?”

Our common

humanity is also emphasized. Beg is told

by a rabbi that Jews are “’a braided rope, individual threads woven to from a

single cord. That’s how we are linked’”

but that connection obviously applies to all humanity. A refugee looks at the body of one of his

fellow travelers and makes a realization:

“What were the differences between them again? He couldn’t remember. It had to be there, that bottomless

difference, but his hands clutched at air.

Now that the delusions had lifted, he saw only how alike they had been

in their suffering and despair.”

Part of

that humanity is an instinct for self-preservation. What people will do to survive is

amazing. The woman in the group resorts

to eating sand. The young boy is

horrified and understands the feral nature of her actions when he says, “’You

can’t eat sand! People don’t eat sand!’” The need to survive means stripping bodies of

their clothing and precludes kindness towards others. When one of the refugees gives some food to another

who is so weak from lack of food that he is struggling to continue, his

compassion is perceived as strange. Even

the one who is saved by the man’s self-sacrifice questions his benefactor: “The black man helped him move along and

supported him when he could go no farther, but that also meant he was to blame

for the way his earthly suffering dragged on.

Gratitude and hateful contempt chased each other like minnows at the

bottom of a pool.” The young boy best summarizes

the disturbing behaviour he witnesses: “And

along his way he has seen almost every sin you could imagine – there are so

many more of them than he’d ever realized!”

As I read

this book, I was reminded of Voltaire’s statement that, “If God did not exist,

it would be necessary to invent Him.” Voltaire was arguing that belief in God is

beneficial and necessary for society to function. The migrants, trying to find meaning in their

circumstances, form beliefs resembling a religion: “a shared conviction took hold.”

One of the travelers justifies their plundering an old woman’s food supplies by

stating, “’She was there for us, so that we could go on.’” They believe they were lead to her by their bodiless

god because “they had been chosen”; Beg questions one of the survivors: “’He was on your side; he was only there for

you people. Not for some feeble-minded

woman; only for you. He allowed you to

rob her of everything she had because you people were his favourites, am I

right?’” Of course this idea of

chosenness is to remind the reader of the belief of the Jews that they are God’s

chosen people.

This novel

could be called a parable for contemporary times. It seems a simple story but has several

messages. A re-reading would undoubtedly

reveal more depths.

No comments:

Post a Comment